The `background` debacle — a case study on web compatibility

- Introduction

- First, a detour: how CSS comes to be

- Authors? Serialization?

- So why was this change made?

- But wait, there’s more!

- Web platform tests: the ultimate equalizer

- Summary

Introduction

A few days ago, I was browsing the CSS Backgrounds 3 spec trying to determine the browser-default background-color of the viewport for use in Kosmonaut (hint: it’s system and browser dependent).

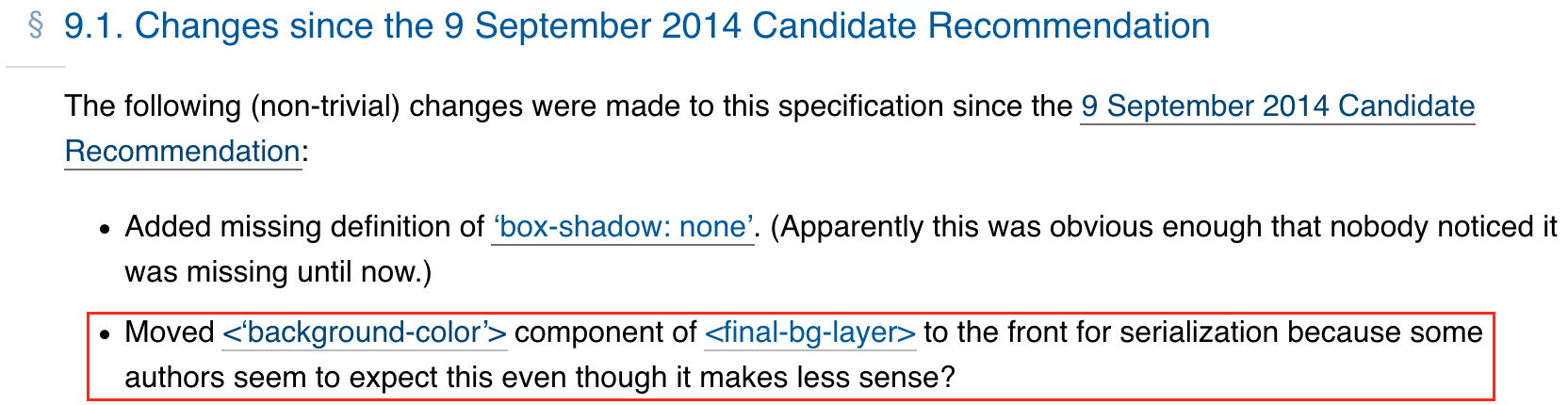

In doing so, I stumbled across this note in the changelog:

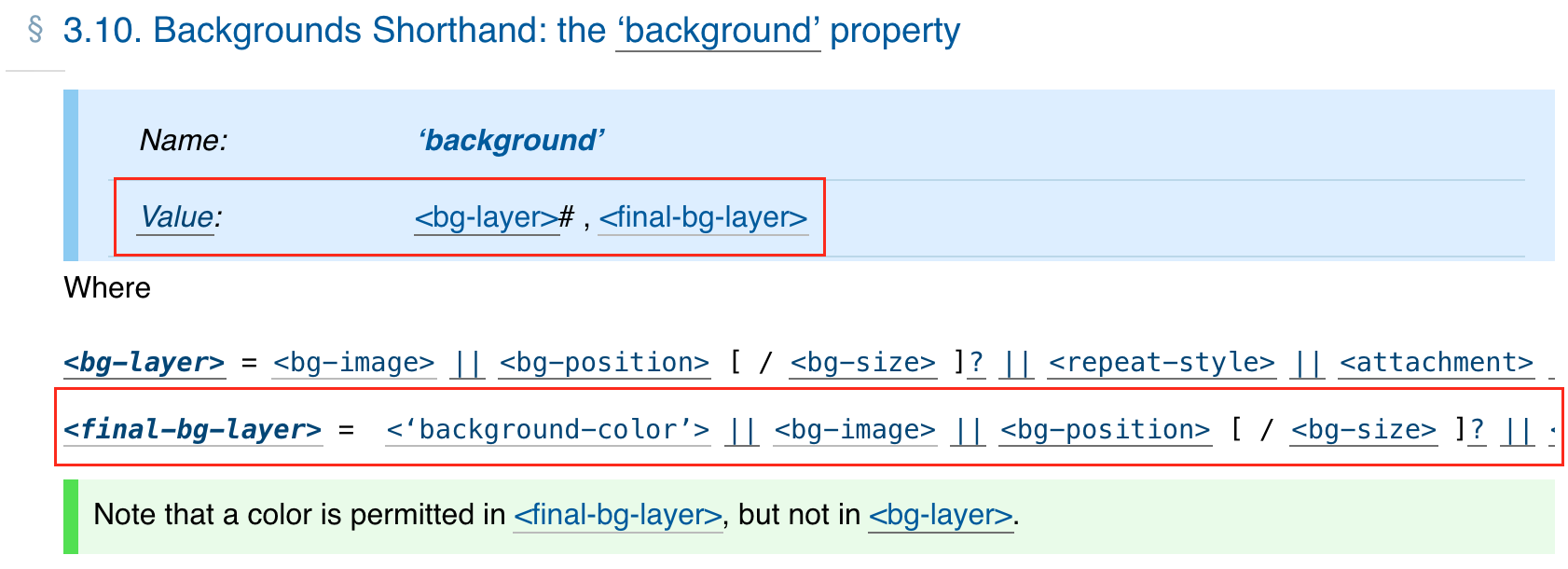

Clicking into the <final-bg-layer> hyperlink, we discover this revision changed the serialization order of the background shorthand property:

# next to <bg-layer> means "0 or more" non-final background layersThis intrigued me. Why do authors expect the color to be first, and why does it make less sense for the color to be first? What does this change mean in practice? How was this decision to change the specification made?

Read on for a glimpse into how the CSS sausage is made, from CSS specification to (sometimes differing) browser implementation. You can expect to learn about the CSS standards process, CSS serialization, web platform tests, and more, hopefully gaining some appreciation for the difficult task that is web compatibility.

First, a detour: how CSS comes to be

Having an understanding of how the CSS standards process works will help in understanding the background shorthand awkwardness, so let’s go over it.

In summary: CSS syntax is standardized by the CSSWG (CSS working group), which is comprised of representatives from browser vendors, universities, various companies, and some independent experts. New CSS syntax passes through six stages:

-

Editor's draft (ED)

New syntax goes from idea to "paper" in this phase, during which it is fleshed out internally by the CSSWG. You can find WIP editor drafts here: https://drafts.csswg.org/ -

Working draft (WD)

If an ED is accepted internally by the CSSWG, it moves onto this phase for review by the community (technical organizations, W3C members, the public). Changes to the specification continue to be made during this phase. You can find the current working drafts (and more) here: https://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/current-work.en.html -

Last call working draft (LCWD)

The LCWD provides a hard deadline for any final changes to a WD before it moves on to the CR phase. -

Candidate recommendation (CR)

Browsers typically implement the specification in this phase in order to gain implementation experience, thus determining the worthiness of this specification for the final phases. We see this phase mentioned in the above screenshot, meaning the change tobackgroundserialization we will dive into shortly was a revision to the original CR. -

Proposed recommendation (PR)

The W3C Advisory Committee decides if the specification should move to the final phase. -

Recommendation (REC)

The specification is considered complete and ready to implement. Only small maintenance work happens at this phase. In reality, most browsers implement specifications at the CR phase, so specifications that make here are often "dead", laden with errors discovered in implementation that are too difficult to fix in these later phases.

The above is largely a summary of this article, so head there if you’re looking for more detail.

Authors? Serialization?

Before we continue, allow me to clarify some terms you might not be familiar with.

Moved <background-color> component of <final-bg-layer> to the front for serialization because some authors seem to expect this even though it makes less sense?

In the context of CSS specifications, “authors” are the authors of webpages — web developers. You may also see the terminology “implementor” — these are the people implementing the specification, so browser (which is also known as a user agent) developers.

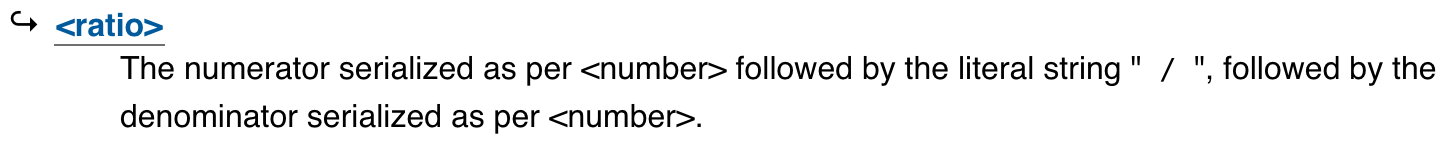

Serialization is the process of converting from a data structure (e.g. Rust struct, C++ class) representation of a CSS object to a string representation of that CSS object. To see this more concretely, check out this portion of the CSSOM (CSS Object Model) spec that details how to serialize various CSS values and components. Here’s an excerpt showing the serialization of a <ratio> value:

Whenever you ask the browser for state on styles, such as through the HTMLElement.style or Window.getComputedStyle APIs, the value it returns to you is the result of the serialization of its data structures to a string.

It’s important to note that how you input styles for an element may not be how they are later serialized back to you. In fact, this point is the crux of the issue we’re exploring — the serialization of the background shorthand property differed from author’s expectations based on previous browser behavior and the spec.

For example, given this specified style:

#target {

background: url("https://bit.ly/") 1px 2px / 3px 4px

space round local padding-box content-box,

rgb(5, 6, 7) url("https://bit.ly/") 1px 2px / 3px 4px

space round local padding-box content-box;

}You might get back this (or something completely different, depending on your browser) post-serialization:

const target = document.getElementById('target')

console.log(target.style['background'])

// Logs the following.

// Note the difference in order vs. what was specified above.

// url("https://bit.ly/") space round local

// 1px 2px / 3px 4px padding-box content-box,

// rgb(5, 6, 7) url("https://bit.ly/") space round local

// 1px 2px / 3px 4px padding-box content-boxThe order in which properties are serialized could be very important. For example, perhaps you are writing a JavaScript framework that parses the serialized styles of HTML elements in order to compute some new ones. Different serializations in different browsers makes this much, much more difficult to do.

So why was this change made?

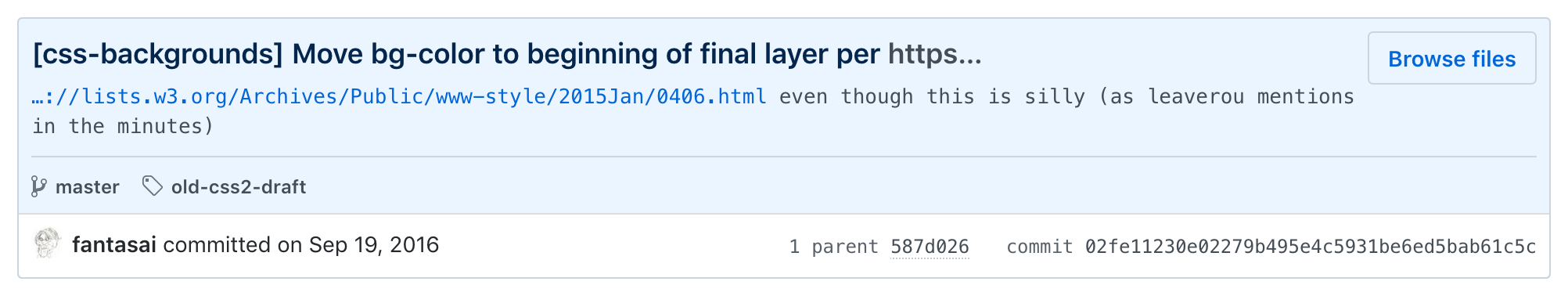

Development of these specifications happens on Github, so let’s look at the commit that introduced this change:

Clicking on the pictured hyperlink takes us to a set of CSSWG telecon meeting notes from 2015. Search for “background serialization” to find the bit we’re interested in.

Feel free to read the full conversation yourself — for the sake of brevity, here is a summary of points:

-

The CSS 2.1 background spec placed the

<background-color>first in the<final-background-layer>value list. -

For CSS3, the

<background-color>was moved to the end of the<final-background-layer>because it is painted underneath all the other components of this layer (e.g. the background image and all its modifiers). -

Authors complained about this change in serialization, as tutorials had codified the CSS 2.1 serialization order (

<background-color>first). -

It is discovered Chrome's

backgroundshorthand serialization is "100% broken". While not made as explicit in the conversation, WebKit (Safari's browser engine) and Gecko (Firefox's browser engine) likely had, and may still have problems relative to the spec — more on that later.

But wait, there’s more!

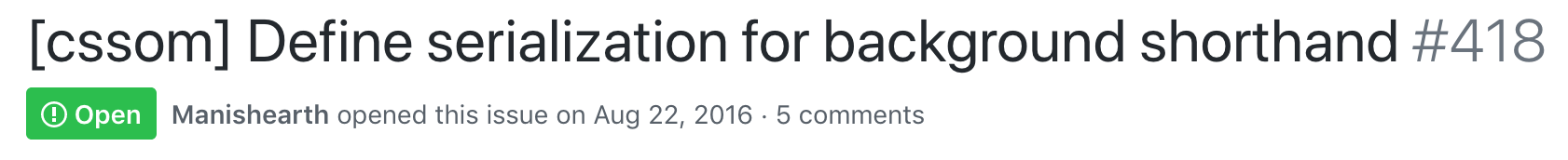

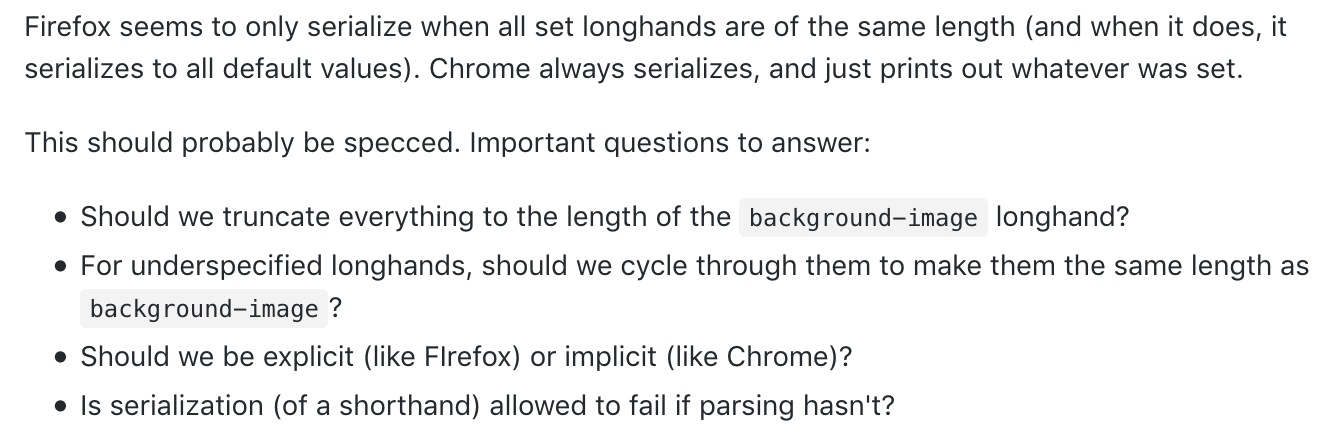

The 2015/2016 spec revision was not the only confusion surrounding background serialization — the topic was also raised as an issue in the CSSWG repository:

And roughly two years after this issue was opened, it was noted in a comment that this inconsistency across browsers still existed. In fact, the linked comment shows all browsers serialized background wrong relative to the spec, each in different ways.

Web platform tests: the ultimate equalizer

There is a somewhat happy ending to this story, and it comes thanks to something called a web platform test (WPT). Quoting the WPT project readme:

The web-platform-tests project is a cross-browser test suite for the Web-platform stack. Writing tests in a way that allows them to be run in all browsers gives browser projects confidence that they are shipping software that is compatible with other implementations, and that later implementations will be compatible with their implementations.

Most browsers automatically sync these tests to their own repositories and use them to help prevent any set of changes from accidentally regressing web-compatibility. At the time of this post, there are a whopping 41,492 WPTs, each of which made up of one or more subtests, for a grand total of 1,711,211 subtests. That’s a lot!

The web-platform-tests group also maintains a website called wpt.fyi, which provides a dashboard to view the results of any and all WPTs for the included browsers.

As you might now be guessing, a WPT was created to more rigidly enforce all the various ways the background shorthand property may be serialized. This is still not ideal, as the test considers five different serializations (spec, Edge, Firefox, Blink, and WebKit) valid, but it’s a great step forward. With this test in place, it’s at least made clear to authors what serializations they could and should expect if they decide to rely on this API.

Making use of the aforementioned dashboard, we can view the results of this WPT for each browser — as is expected, all pass!

Summary

In summary, web compatibility is hard. Thank your local browser developer when you next get a chance :)

If you have any questions, comments, or corrections, feel free to open up an issue or leave a comment below via utterances.

For some extra credit reading, check out this discussion concerning the serialization of computed CSS styles returned from Window.getComputedStyle. There’s some interesting back-and-forth on the validity of serializing the object to an empty string vs. something “meaningful”, and the technical difficulties that would come with that.