RISC-V from scratch 4: Creating a function prologue for our UART driver (2 / 3)

- Introduction

- Setup

- A prologue to function prologues (and epilogues)

- The what and why of ABIs

- Implementing a function prologue

- What about

uart_get_char? - Conclusion

Introduction

Welcome to the fourth post in the RISC-V from scratch series! As a quick recap, throughout RISC-V from scratch we will explore various low-level concepts (compilation and linking, primitive runtimes, assembly, and more), typically through the lens of RISC-V and its ecosystem.

If this is the first post you’ve tuned in to, here is a recap of the previous posts in this series:

- RISC-V from scratch 1: Introduction, toolchain setup, and hello world!

An introduction to RISC-V, RISC-V GNU toolchain setup, and the running of a simple program on an emulated RISC-V processor. - RISC-V from scratch 2: Hardware layouts, linker scripts, and C runtimes

A review of the devicetree layout of thevirtQEMU virtual machine, linker scripts, basic RISC-V assembly, a minimal C runtime, and more, all in an effort to understand how we get to themainfunction. - RISC-V from scratch 3: Writing a UART driver in assembly (1 / 3)

The beginning of an implementation of a driver for thevirtonboard UART, discussing basic UART functionality and doing additional linker script and devicetree layout exploration along the way.

In this post, we will discuss and implement a function prologue for our driver functions uart_get_char and uart_put_char. Function prologues have several important duties, such as ensuring variables stored on the stack for one function call don’t overwrite those of another function call. We’ll walk through a function prologue instruction-by-instruction, diagramming changes to the stack and registers along the way.

Setup

If you have worked through all the previous posts in this series, you can cd to your riscv-from-scratch directory and skip this section. If you’re new to this series and would like to follow along, keep reading!

- Follow these instructions from the first post to install the GNU RISC-V toolchain and a version of QEMU with RISC-V emulation capabilities.

- Clone or fork the riscv-from-scratch repo:

git clone git@github.com:twilco/riscv-from-scratch.git

# or `git clone https://github.com/twilco/riscv-from-scratch.git` to clone

# via HTTPS rather than SSH

# alternatively, if you are a GitHub user, you can fork this repo.

# https://help.github.com/en/articles/fork-a-repo

cd riscv-from-scratch- Check out the

pre-function-prologue-implbranch which contains the code prerequisites for this post in thesrcdirectory:

git checkout pre-function-prologue-impl- Copy the customized linker script

riscv64-virt.ld, minimal C runtimecrt0.s, NS16550A UART driver skeletonns16550a.s, andmain.cto our working directory:

# note: this will overwrite any existing files you may have in `work`

cp -a src/. workA prologue to function prologues (and epilogues)

In the previous post, we codified the base memory address of the onboard virt UART as the __uart_base_addr symbol. We can use this symbol to access the internal registers of the UART, as the address of each register is an offset of the base address. However, before making use of these registers to begin the actual implementation of our UART functions, there’s one more important topic we’ll need to discuss: function prologues.

In most high-level languages, variables that are passed into functions are, when necessary, stored on the stack. The compiler or interpreter does a lot of work to make this process seamless. They save you from having to worry about:

- How variables get saved onto the stack

- Ensuring variables from one functions stack don't overwrite that of another functions stack

- The mechanism for returning execution from the callee to caller when a function has completed

- Cleaning up unneeded variables from the stack for functions that have completed

There are standard solutions for these standard problems: function prologues and function epilogues. Function prologues address the top two concerns, and function epilogues address the bottom two concerns. This is one thing that makes the function definition syntax in higher-level languages so important - if necessary, the compiler or interpreter will insert a function prologue and epilogue for you when generating the IR or assembly representation of your function.

There are two important registers we’ll need to become familiar with: the stack pointer, sp, and the frame pointer, fp. In the RISC-V ABI, the stack pointer points to the next available memory location on the stack, and the frame pointer points to the base of the stack frame.

You can think of a stack frame as a dedicated scratch space on the stack for variables passed in upon invocation of a function. It’s the function prologue’s job to:

- Establish this stack frame

- Save variables passed into the function onto the stack at some memory address offset of the stack frame base (the frame pointer)

The function prologue is also responsible for saving the caller’s frame pointer. This is important because when we return control to the caller in the function epilogue we must also restore their frame pointer. More on this later.

The what and why of ABIs

Before implementing our function prologue, we need to alter our main.c file to pass a byte into uart_put_char so we have a parameter to work with.

int main() {

// 0b00000010 == 2 == 0x2

uart_put_char(0b00000010);

}We’re now passing a variable into uart_put_char from our C program. But wait, uart_put_char is simply an assembly symbol…how exactly do we get at this parameter? Assembly doesn’t have any concept of functions or parameters.

Answering this question requires us to learn more about application binary interfaces, or ABIs. ABIs standardize some very important things, such as the length of each data type (is an int 8, 16, 32, or 64 bits?), whether the stack grows up or grows down, and the expected calling convention that should be followed. Calling conventions determine how functions receive parameters from and return results to their caller.

RISC-V has quite a few ABIs, such as ilp32 (integer long pointer 32-bit) and ilp32d (integer long pointer 32-bit double). In all RISC-V ABIs, function parameters 0-7 are passed in registers a0 through a7, with registers a0 and a1 also serving as the place for return values to be passed back to the caller. Also, in all RISC-V ABIs, the stack grows down from higher addresses to lower addresses, so from 0x88000000 down to 0x80000000 in our virt QEMU machine.

Bringing the discussion back to our main function, this means we know we can find the input parameter to uart_put_char in register a0, as that is what the ABI dictates.

Implementing a function prologue

One other final thing to note before we begin our function prologue: we’ll be implementing these functions as if we were a compiler with no optimizations enabled, which is -O0 in the GCC world. This means we’ll ignore some easy optimizations and do a lot of unnecessary work, such as unconditionally spilling all registers onto the stack, in the name of education.

So, without further ado, here is the entire function prologue for uart_put_char:

uart_put_char:

.cfi_startproc

# create 32 bytes of space on stack

addi sp,sp,-32

# store callers frame pointer inside the newly created stack frame

sd fp,24(sp)

# set the frame pointer to the beginning of the stack frame

addi fp,sp,32

# copies register a0 into register a5 to sign-extend our single byte input

# this is required by the RISC-V calling convention

# https://github.com/riscv/riscv-elf-psabi-doc/blob/master/riscv-elf.md#-integer-calling-convention

# mv is a pseudoinstruction that expands to: addi a5,a0,0

mv a5,a0

# copies least-significant byte of register a5 onto the stack at

# address (frame pointer - 17 bytes)

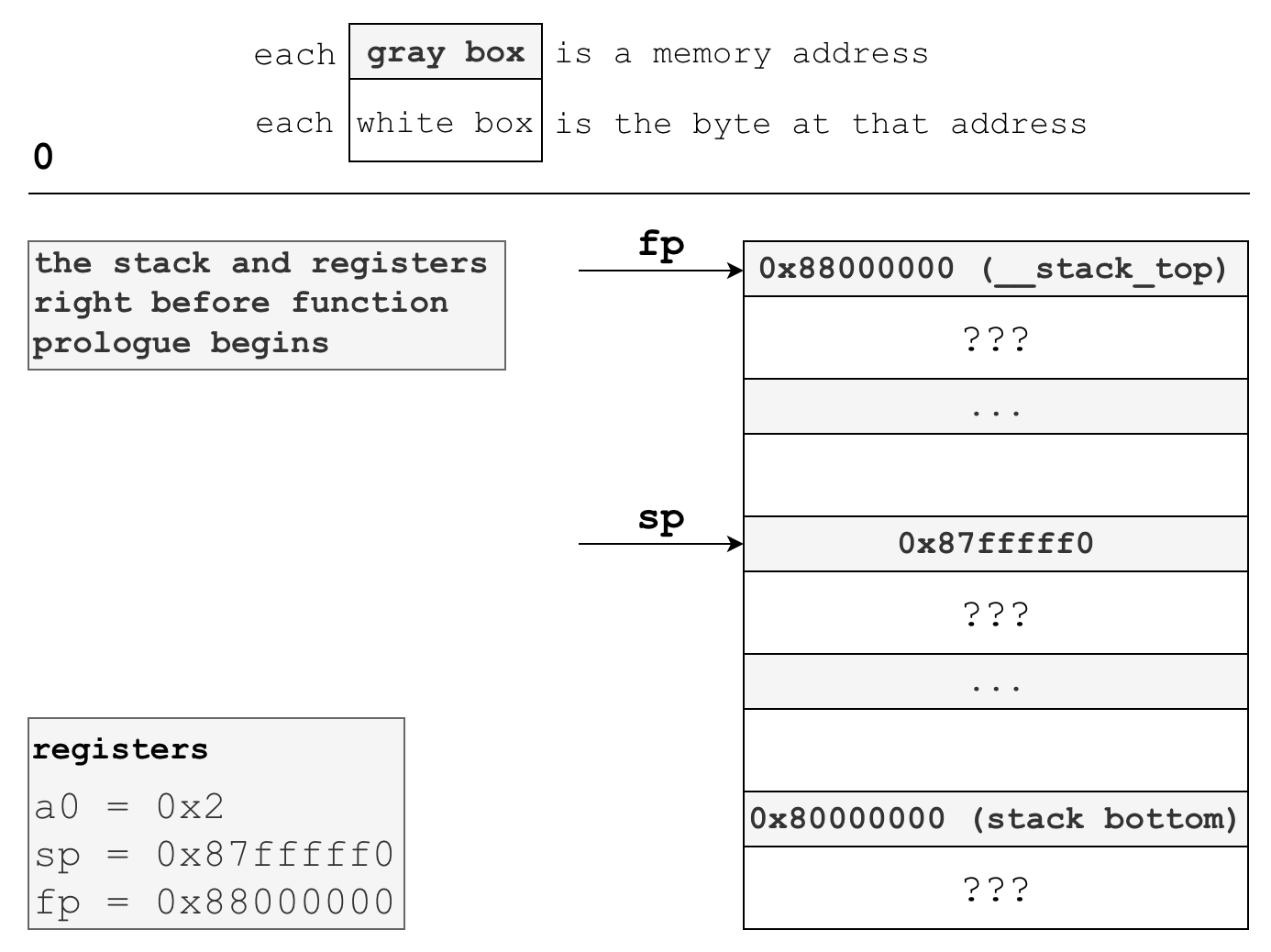

sb a5,-17(s0) And here’s what the stack and registers might look like right before our uart_put_char function prologue:

Note that the a0 register has the 0x2 value we passed from main above. Also, sp and fp have values set by whatever calls this function - I have assigned them realistic values for the sake of demonstration.

Let’s run through this prologue line-by-line.

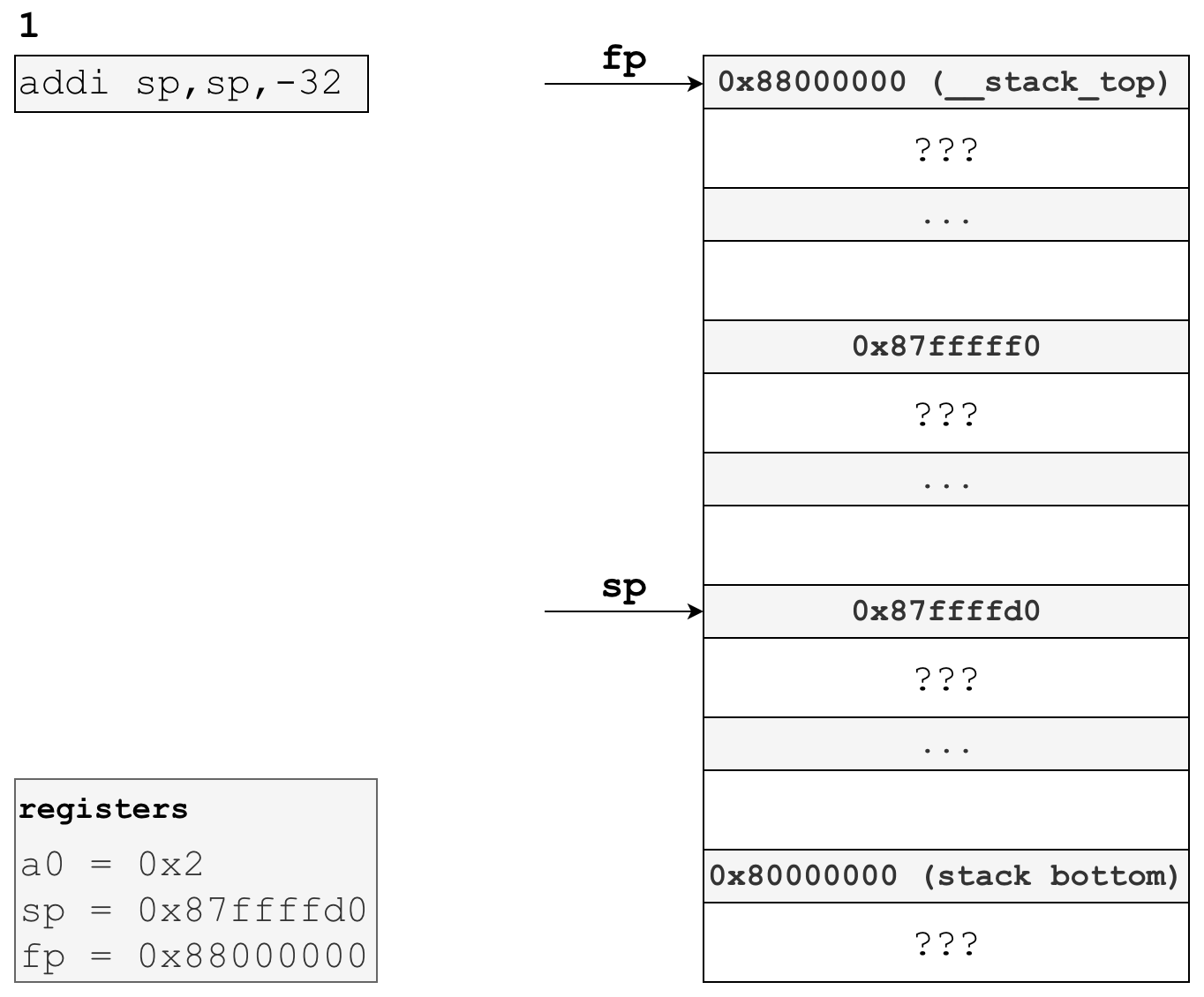

# create 32 bytes of space on stack

addi sp,sp,-32 As you may recall, the stack pointer points to the next free-for-use byte on the stack. By moving this down by 32 bytes, we’re “allocating” space for ourselves on the stack, or creating a stack frame, for later use in this function. Here’s what the stack and registers would look like following this instruction:

All the space between the old stack pointer position (0x87fffff0) and the new stack pointer position (0x87ffffd0) is this functions stack frame.

On to the next line:

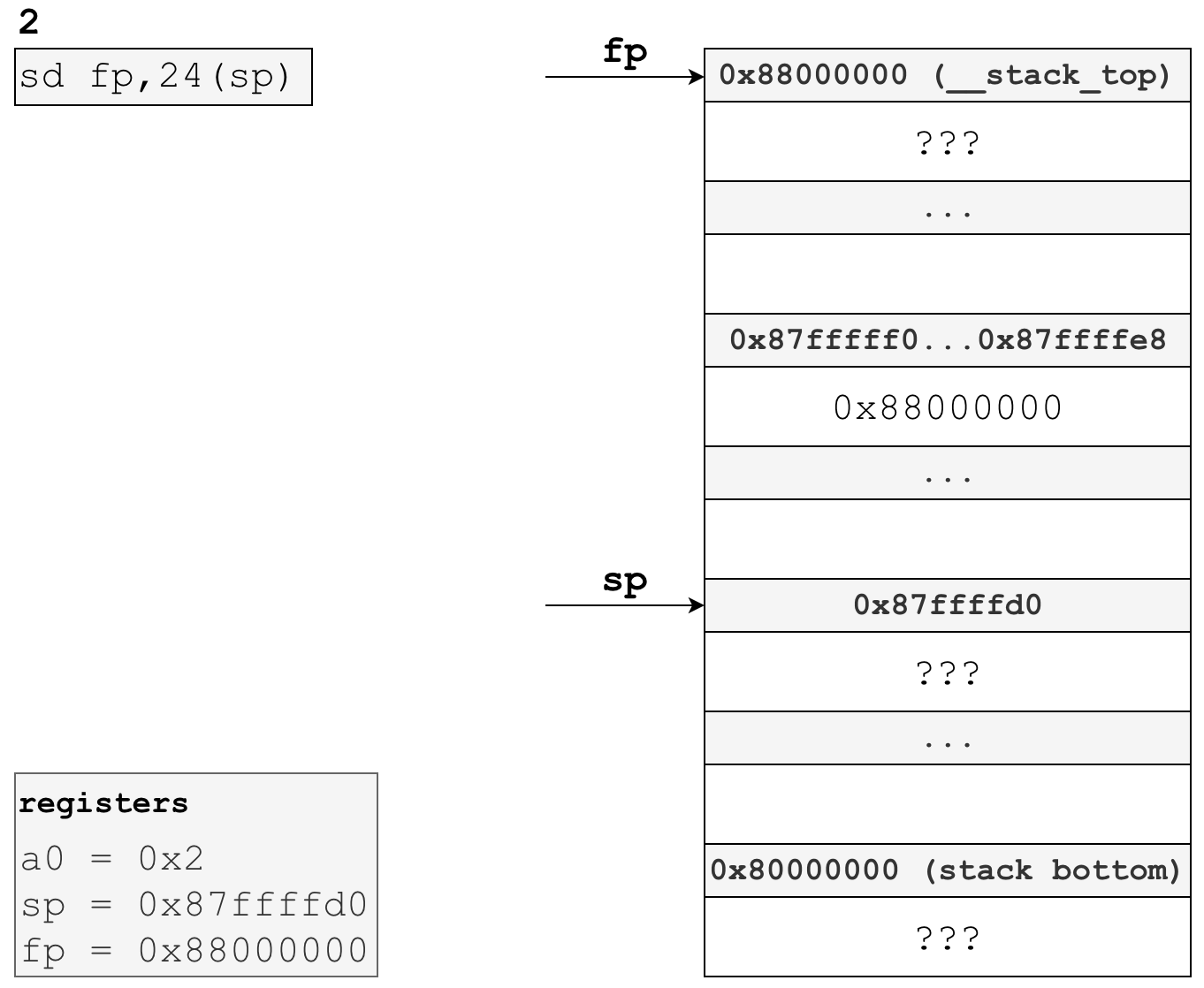

# store callers frame pointer inside the newly created stack frame

sd fp,24(sp)Another thing ABIs specify is what registers the caller is responsible for saving, and what registers the callee is responsible for saving. The fp register, which is also commonly called the s0 register, is a callee-saved register.

So, to acommodate that requirement we make use of the sd instruction, which stands for “store doubleword”. This instruction moves the eight bytes (a double word) in fp to the stack at memory address 24 + sp. What this effectively does is save the caller’s frame pointer, 0x88000000, at address 0x87ffffd0 + 24 = 0x87ffffe8.

Here’s what the stack would look like after executing this instruction:

As you can see, we now have the caller’s frame pointer saved in 0x87ffffe8, specifically in the 8 bytes from 0x87fffff0 to 0x87ffffe8. We’ll need this later in the function epilogue when we restore this value before returning control to the caller.

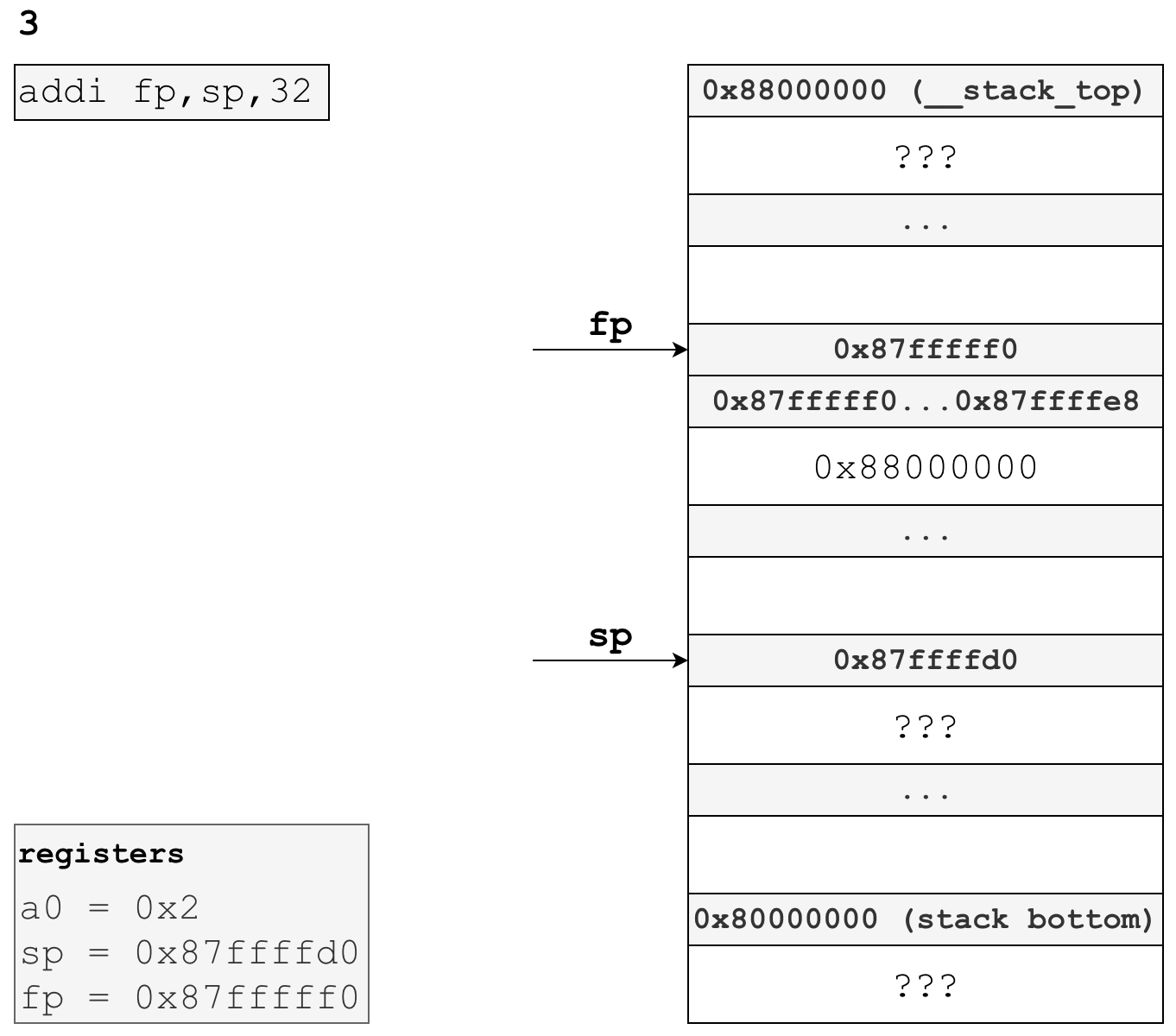

On to the third line in our function prologue:

# set the frame pointer to the beginning of the stack frame

addi fp,sp,32As you can see in the previous image, the frame pointer is still set to caller’s frame pointer. addi fp,sp,32 adds the decimal value of 32 to the current of the stack pointer, 0x87ffffd0, and stores the result in our fp register. Following this instruction, our stack frame is officially set up - fp points to the base address of our stack frame, and any space between fp and sp is scratch space for this specific function invocation. We have already allocated the first 8 bytes in this stack frame to store the caller’s frame pointer, and we will use more later when we store the single input parameter we have for this function.

Following this instruction, the stack and registers now look like this:

Our next instruction is this:

# copies register a0 into register a5 to extend our single byte input

# this is required by the RISC-V calling convention

# https://github.com/riscv/riscv-elf-psabi-doc/blob/master/riscv-elf.md#-integer-calling-convention

# mv is a pseudoinstruction that expands to: addi a5,a0,0

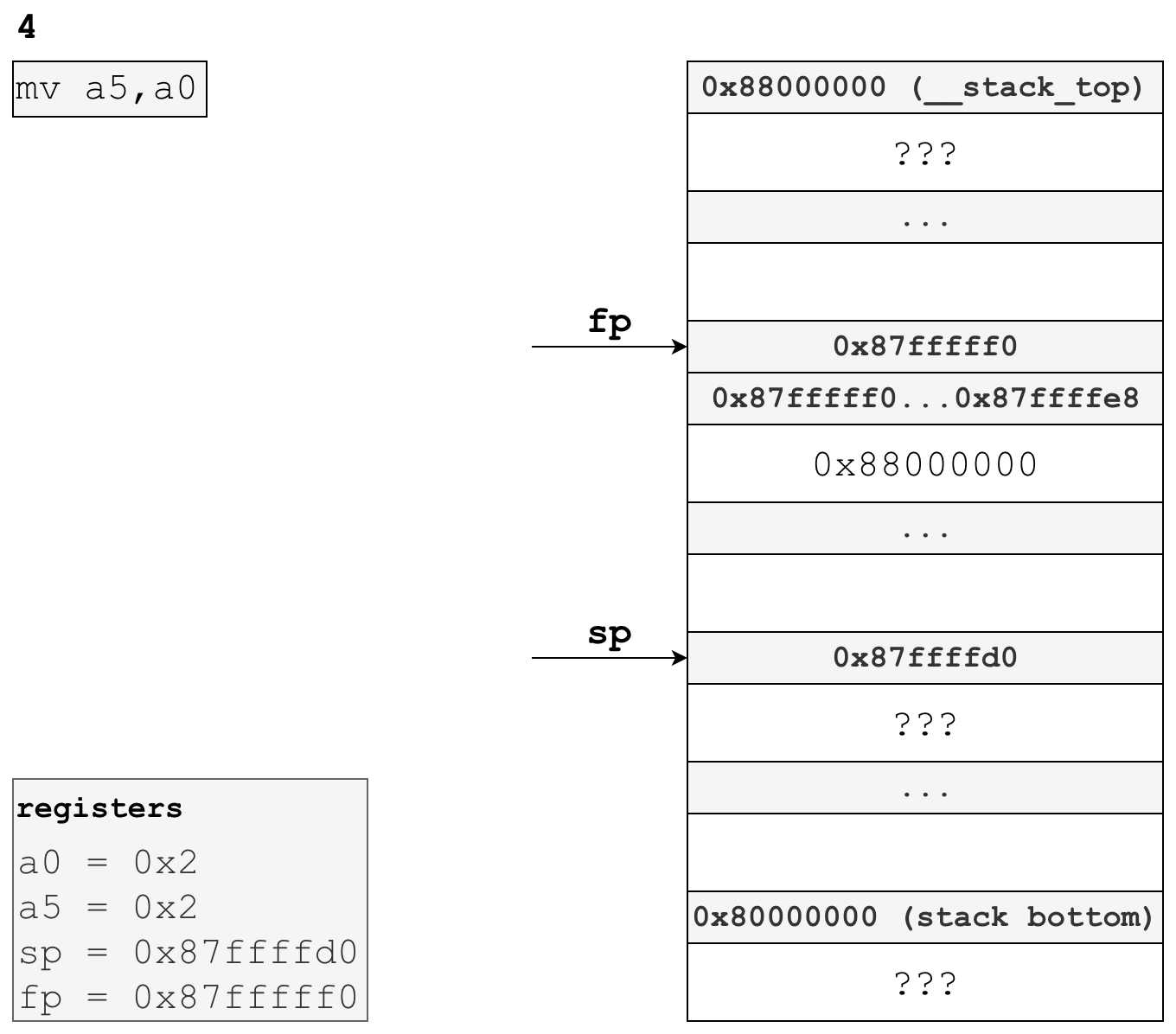

mv a5,a0This instruction moves our first function parameter in a0 to register a5, which is the register for the sixth function parameter. In the final phase of our function prologue, we’ll refer to our input parameter in its new register, a5.

You may find this a little odd — why waste an instruction moving the parameter from one argument register to another, when we could just operate on a0?

It turns out there is a very good reason we do this, and that is scalar extension. The RISC-V integer calling convention requires that scalars narrower than 32-bits or 64-bits, depending on which compiler you use, must be extended:

When passed in registers, scalars narrower than XLEN bits are widened according to the sign of their type up to 32 bits, then sign-extended to XLEN bits.

Our function parameter 0b00000010 is 8 bits, which requires us to widen it.

Coming back to our instruction mv a5,a0, mv is a pseudoinstruction that expands to addi a5,a0,0, adding a0 to the literal value of zero and storing the result in register a5. addi also sign extends the literal zero immediate value before adding it to a0, meaning the resulting value stored in a5 will be widened as is required by the ABI.

Following this instruction, the stack and registers now look like this:

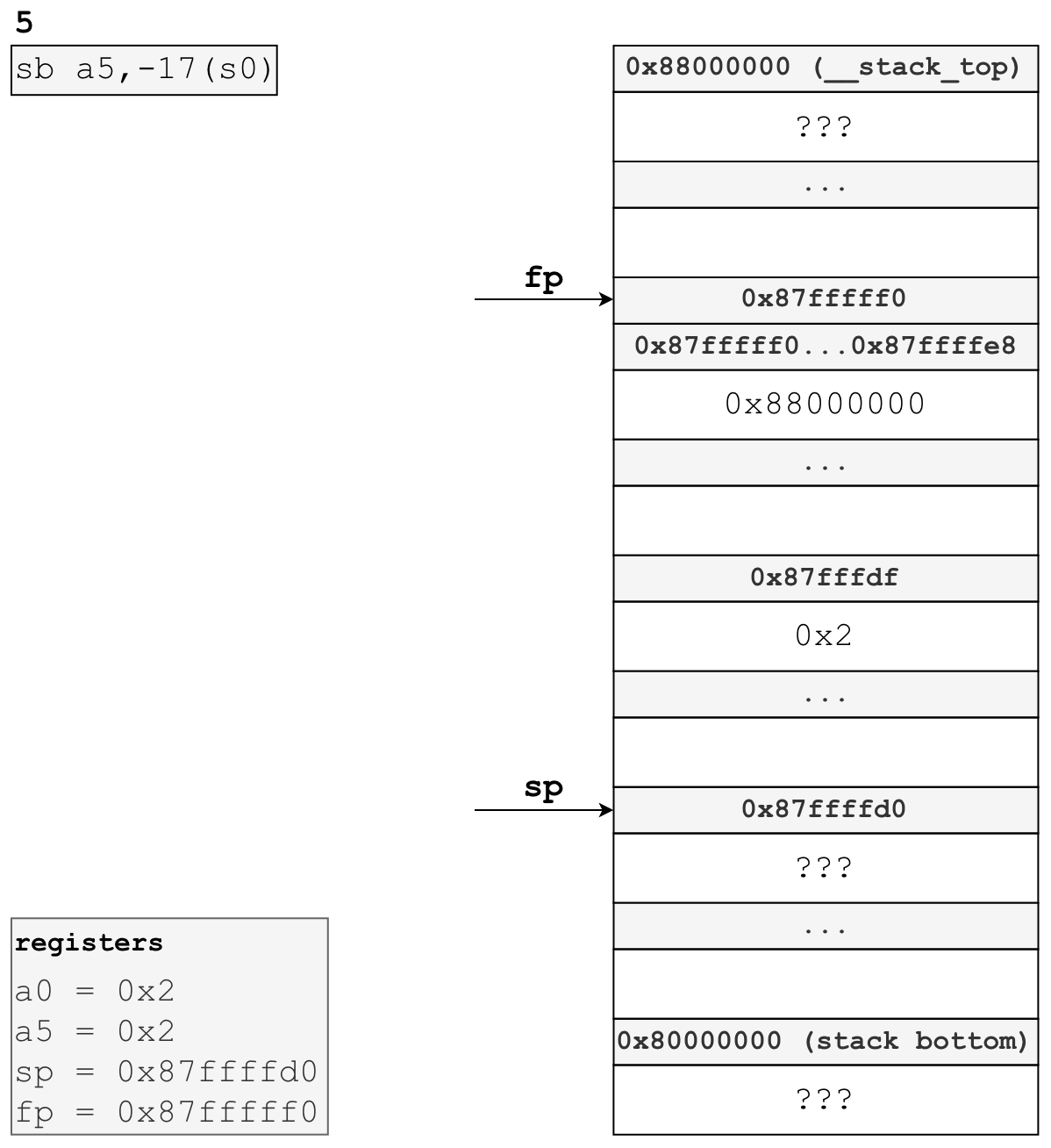

This brings us to the final instruction in our function prologue:

# copies least-significant byte of register a5 onto the stack at

# address (frame pointer - 17 bytes)

sb a5,-17(s0) sb, store byte, saves the least-significant byte of a5, which we know to be 00000010, onto the stack. Recall that we are writing this prologue as if we were a compiler with no optimizations enabled (-O0 for GCC), meaning we unconditionally spill all registers to the stack. In this unoptimized world, we would then reload this byte from the stack into a register with lbu, load byte unsigned, when we want to work with it in the function body.

After this instruction, our stack and registers will look like this:

And that’s the function prologue for uart_put_char! In summary, we “allocated” a stack frame by moving the sp and fp, saved the caller’s fp as required by the ABI, and sign-extended and saved our input parameter to the stack for later use in the function body.

What about uart_get_char?

The function prologue for uart_get_char will be much simpler since it doesn’t take any input parameters. Here it is:

uart_get_char:

.cfi_startproc

# move the stack pointer down 16 bytes to allocate

# space for our stack frame

addi sp,sp,-16

# save the callers frame pointer onto the stack

sd s0,8(sp)

# move the frame pointer to the base address of this stack frame

addi s0,sp,16This should look quite familiar - all we need to do is establish our stack frame and save the caller’s frame pointer inside that stack frame for use in the function epilogue.

If you’re like me and wondered why we allocate 16 bytes of space when we only need 8 bytes to store the caller’s frame pointer, your answer is here:

…stacks tend to be allocated conservatively, which means they’re aligned to the largest type that can be spilled to the stack. On RISC-V, this is 16 bytes.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve successfully created a pair of unoptimized function prologues that set us up for success in our upcoming implementation of a function body and epilogue for uart_put_char and uart_get_char. We learned about several new RISC-V assembly instructions and explored various concepts such as ABIs, calling conventions, stack spilling, and more. Hopefully you learned a lot — I certainly did!

If you’d like more of this, play around with the compiler explorer, which shows you what assembly will be produced by various different compilers. This tool separately highlights the sections of assembly for the function prologue, body, and epilogue, and allows you to pass any combination of compiler flags. For a fun experiment, try comparing the difference between the function prologue of a simple C function with no optimization, -O0, and higher levels of optimization, such as -O1.

When the next post is complete I’ll link it here. If you have any questions, comments, or corrections, feel free to open up an issue or leave a comment below via utterances.

Thanks for reading — hope to see you in the next post!